Three experts from UNS take us through how cognitive science, neuroaesthetics, and workplace design strategies are reshaping hybrid offices to enhance focus, reduce stress, and attract employees back to the workplace.

Going to the office, once a default, is now a choice – and users are choosing differently. Even with beautifully designed spaces and flexible policies, companies are struggling to offer a compelling reason to come into the workplace. Why? People feel more in control of their environment, energy, and attention when at home.

Home has become the go-to setting for deep focus, administrative tasks, creative solo work, or virtually anything that benefits from quiet, autonomy, and flexibility. The office, in turn, is increasingly reserved for what is harder to replicate remotely: in-person meetings, presentations, or spontaneous collaboration. This intentional division of labor is reshaping how, when, and where people choose to work.

Despite workplace redesigns and increased flexibility, Gallup reports that nearly 60% of remote-capable employees favor hybrid arrangements, with only 20% wanting to return to the office full-time. The issue is not only operational, it is experiential. The modern office must offer a cognitive and emotional experience that competes with, and complements, the comforts of home.

To address this opportunity, workplace design needs to move beyond aesthetics and amenities. We know what employees expect from the office, and while some tasks may seem easiest to complete at home, the right environment can actually improve them in the office. This is where cognitive science, particularly research into neuroaesthetics, attention, and sensory processing, offers powerful tools to create environments that feel better, function better, and support the full spectrum of evolving work activities.

The question is:

how can we, as architects and designers, translate these cognitive insights into spatial strategies that actually change behavior?

At UNS, our in-house experience design team works closely with designers to bridge design and cognitive psychology, particularly for envisioning environments that respond to how the brain processes space, light, sound, and social cues. Across multiple typologies, including recent workplace projects, we have been integrating findings from cognitive science to shape environments that not only look beautiful but also actively support focus, creativity, recovery, and emotional regulation. These strategies are proving essential for making the office not just a place to work, but a better place to think.

The emotional logic of working from home or in-office

Work-from-home appeals because it allows people to self-regulate their environment, conserve energy, and avoid the sensory and social overload of traditional office settings. In many ways, the home supports the brain’s need for clarity, calm, and flexibility.

This makes one thing clear:

bringing people back to the office is not about replicating their homes, it is about designing something cognitively superior.

To do that, we need to address the core reasons people avoid the office in the first place, using design as a form of behavioral scaffolding through three powerful, yet underutilized, cognitive design strategies: cognitive contrast, sensory budgeting, and productive mind-wandering.

Designing for cognitive contrast

Many contemporary offices, while aesthetically refined, often present a consistent sensory tone across different zones, but the brain thrives on difference. Shifting between work modes such as deep focus, casual collaboration, or creative ideation, requires the brain to context switch, and this process benefits greatly from environmental cues that support that mental transition.

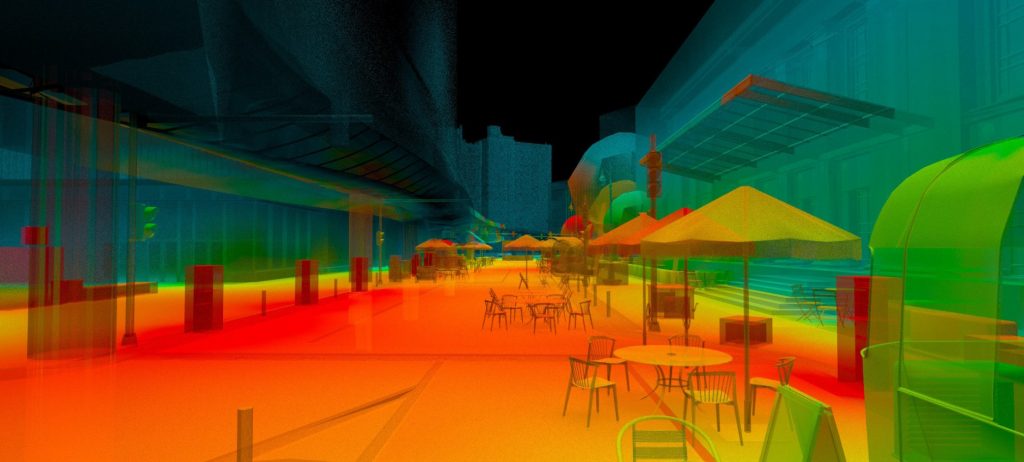

Designing for cognitive contrast means intentionally embedding moments of spatial variation such as changes in ceiling height, material texture, acoustic profile, lighting tone, or layout density, to signal a shift in mental mode. This might look like a narrow, dim corridor leading into an open, light-filled ideation space, or a tactile wall finish that marks the entry into a deep-focus zone. These transitions provide what neuroscientists call contextual boundaries, visual and sensory signposts that help the brain compartmentalize tasks and recover faster between them.

In practice, we have applied this thinking in office designs where different work zones are characterized by distinct spatial identities, rather than one continuous aesthetic. This not only supports a wider range of work styles, but also helps workers mentally ‘reset’ as they move through the day.

Designing for sensory budgeting

The open office was meant to increase collaboration, but often it is just loud, distracting, and visually chaotic. This leads to cognitive overload, where the brain’s limited processing resources are depleted by managing irrelevant stimuli. In this state, attention suffers, decision fatigue sets in, and stress levels rise.

By drawing from cognitive ergonomics, similar to how digital UX designers consider mental load, we can design physical spaces that conserve neural energy. We call this sensory budgeting: treating every sensory input as something that either taxes or supports the brain’s limited attention bandwidth.

This might mean limiting visual clutter through clean sight lines and low-contrast material palettes in focused zones, incorporating controlled soundscapes to mask disruptive noise, or using natural ventilation and scent to reduce environmental stressors. It is also about offering zones with different sensory intensities, giving people options to retreat or engage depending on their needs.

An example of this are designs with a quiet area buffered from ambient noise by a transitional zone, featuring soft flooring and curved walls. This small intervention, inspired by sensory gating research, helps reduce overstimulation and provides a subtle cue that one is entering a cognitively restorative zone.

Designing for productive mind-wandering

Not all productivity happens in high-focus zones. Neuroscience shows that some of our most creative and high-level thinking occurs during periods of mind-wandering, when the brain enters the ‘default mode network’, a state associated with memory consolidation, problem-solving, and idea generation.

Workspaces that support this mode do not have to look like traditional brainstorming areas. Instead, they should foster moments of ease, visual interest, and movement, qualities we often see in hospitality and wellness environments. Soft lighting gradients, biophilic elements, artworks in peripheral view, and curved pathways can all support this kind of relaxed attention.

We are learning from sectors like hospitality, where lobbies and lounges are designed to promote comfort, curiosity, and emotional engagement. By applying these cues to workplace common areas, we can create more emotionally intelligent spaces, those that allow the brain to shift gears naturally, without always being “on.”

Reimagining the office as a place people want to be

If the office is to remain relevant in the age of remote work, it must offer more than infrastructure, it must offer cognitive value. Environments should help workers transition between modes of work, conserve their mental energy, and access deeper states of creativity and reflection. These are not just lofty goals, they are actionable design strategies backed by neuroscience and behavioral psychology.

The role of the designer, then, is evolving. We’re not just shaping spaces, we are shaping experiences that resonate with how the human mind works. By integrating cross-disciplinary insights and drawing lessons from other industries, we can create workplaces that people do not just have to return to, but actually want to.