In workplace design, art is often treated as a final touch: a static object chosen to complement finishes and furniture. Yet workplaces are anything but static; they are highly dynamic ecosystems. Culture shifts, people come and go, and organizations evolve.

The question for workplace teams is how to embed that sense of change into the built environment. Art can play a role when it is approached not as decoration, but as cultural infrastructure – a system that reflects identity, fosters dialogue, and adapts over time.

Art as Cultural Infrastructure

Unlike finishes or furnishings, participatory art does not function as a backdrop. It operates more like lighting or acoustics, shaping how people experience space. To achieve this, FYOOG has developed works as frameworks: structures that invite contributions while maintaining clarity and cohesion. With this balance, art becomes an evolving mirror of the community it serves. These contributions also act as an informal channel for organizations to gather insights, surfacing patterns of thought or sentiment in a way that feels voluntary and unpressured, unlike traditional feedback methods.

Modularity as Cultural Expression

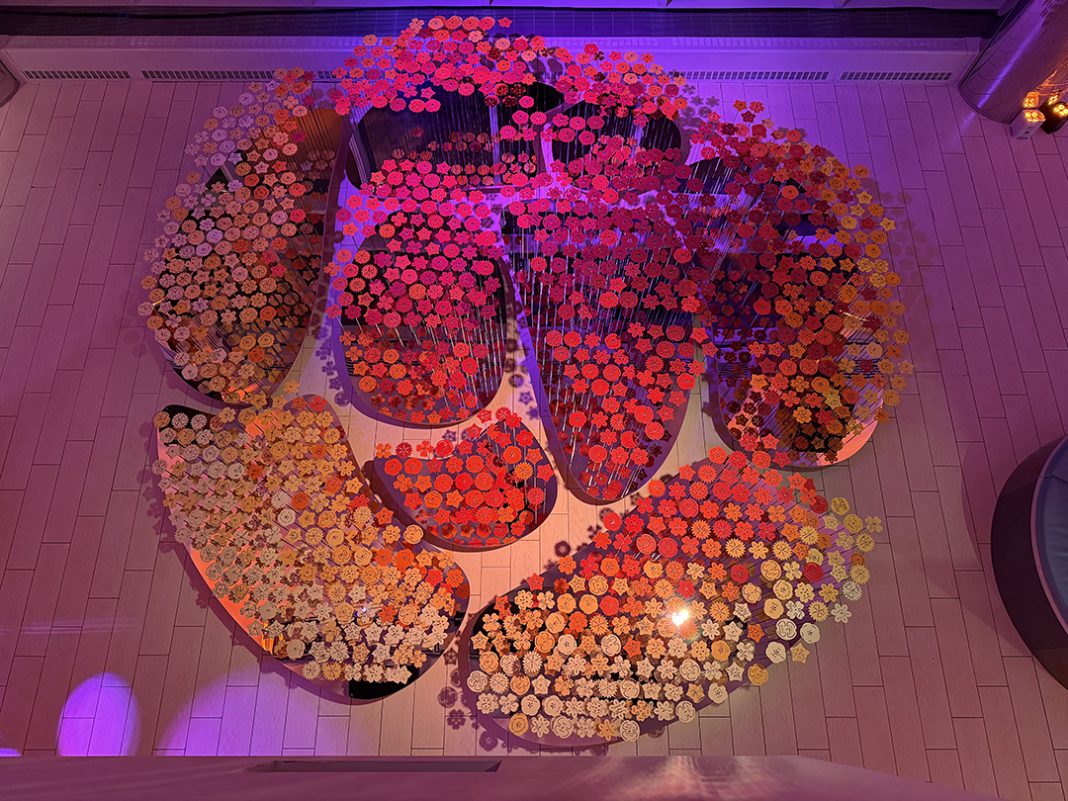

At CoreNet Global 2024, Fleurish illustrated how participatory systems can function as cultural infrastructure. The installation featured bases of wood and mirrored acrylic, planted with slender kite rods at varying heights. Each rod held a vibrant flower-like form made from recycled paper, producing a layered field that shifted in color and density as viewers moved through the space.

The bases were designed to nest in a variety of ways, allowing the installation to expand into broad ribbons, compress into clustered formations, or adapt to unconventional footprints such as lobbies, atriums, or conference halls. This adaptability extended beyond form. Participants’ written reflections transformed the paper flowers into a collective archive, reframing sustainability as more than recycled components. Fleurish demonstrated that sustainability can mean frameworks designed for renewal and reconfiguration, echoing principles of circular design (McDonough & Braungart, Cradle to Cradle, 2002).

Participation Aligned with Programming

At the Society for Human Resource Management 2025 annual conference, a second installation titled Embodied extended this inquiry. The sculptural system consisted of interlocking Baltic birch frameworks fitted with clear acrylic plates, each notched to hold recycled paper flower figures. During FYOOG’s concurrent session on storytelling and organizational culture, participants wrote reflections on the figures and placed them into the structure. By the close of the session, the framework had been filled with hundreds of contributions, creating a living archive of the voices present.

What distinguished Embodied was its integration with programming. The installation was conceived alongside the session itself, ensuring that participants could move immediately from dialogue into visible action. This pairing reflected research showing that shared narratives and storytelling are among the most effective ways to reinforce organizational culture (Denning, The Leader’s Guide to Storytelling, 2011). For workplace practice, this demonstrates how spatial interventions become more powerful when they are tied to rituals and events.

Integrating Participatory Art Into Practice

Workplace projects succeed when participatory systems are considered early in the process. During visioning, teams can map participation goals to spatial types: lobbies as places of welcome and identity, corridors as episodic discovery, and atriums as communal rituals. Early coordination with facilities and operations staff ensures realistic maintenance plans. Fire code and egress reviews prevent late-stage conflicts. Mock-ups can test density, legibility, and refresh cycles before full rollout.

Material choices should support durability and flexibility, while lighting can bring dynamism. Even small adjustments in direction or intensity can animate form and reinforce the sense of ongoing change. Research confirms that dynamic environments improve both well-being and memory.

Operations and Stewardship

Participatory systems thrive with active stewardship. These installations are not static pieces left behind; they require care and periodic renewal. Many organizations now engage FYOOG through subscription or refresh programs, which regularly provide new components and prompts. This approach sustains momentum and ensures the system reflects evolving culture.

Stewardship also involves paying attention to what emerges. Written reflections and engagement patterns can offer leaders a real-time pulse on cultural dynamics, providing insights that complement surveys or formal assessments. Gensler’s workplace research underscores that adaptability and stewardship are as central to resilience as material sustainability.

Budgeting and Long-Term Value

Budgeting for participatory systems should be understood as an investment in cultural infrastructure. Costs extend beyond fabrication to include design, installation, integration, and stewardship. Because the systems are modular and renewable, value accumulates over time rather than expiring at installation. Gallup’s global workplace report notes that only 23% of employees feel engaged at work, underscoring the importance of sustained cultural investments.

Predictable models such as subscriptions or periodic refreshes give organizations clear pathways to maintain engagement. Unlike static artworks, these systems require continuity and partnership to remain effective. Treating them as long-term collaborations preserves both the physical framework and the cultural energy it generates.

Lessons for Design Practice

Projects like Fleurish and Embodied point to several insights for workplace design:

- Design for adaptability. Modular systems extend longevity by adjusting to multiple contexts.

- Balance openness with structure. Frameworks help contributions build into a coherent whole.

- Integrate with programming. Pairing installations with rituals or events reinforces culture through lived action.

- Plan for stewardship. Assign ownership and refresh cycles to ensure sustained use.

- Use participation to gather insights. Contributions can surface themes and sentiments that formal channels may miss.

- Rethink sustainability. Sustainability includes recycled materials but also cultural relevance sustained through renewal and reconfiguration.

Conclusion

Workplaces are remembered not only for how they look, but for how they make people feel. Participatory art offers a way to design environments that embody identity, capture memory, and foster belonging. Rather than serving as static decor, these systems evolve with their communities. They transform art from something to look at into something to live within: a framework for culture that adapts and endures.