Hassell’s Domino Risch explores the changing nature of workplace design and the need for design to focus on the diverse neurological needs of workers.

I am a workplace designer. I spend most of my working life collaborating and communicating – both internally with my team and externally with clients and partners to create highly functional, beautiful workplaces. My work primarily involves communicating to a myriad of people mostly in corporate organisations who don’t understand ‘archi-babble’, translating our ideas into ‘corporate-speak’ and back again – kind of like a universal translator. But perhaps a hidden dimension is that I am, paradoxically, an introvert, albeit one who has learned how to be an extrovert. There are many times when I prefer to spend time on my own, in blissful silence. I enjoy socialising, but I recharge from being on my own. I know when I am all people’d out and have literally run out of words, and in many ways, I am who Susan Cain was writing about in her seminal book Quiet.

In parallel to that recently my 10-year-old daughter has been diagnosed as having Asperger’s Syndrome – a type of autism that primarily effects people in the realms of communication, social understanding and sensory sensitivity. I know some people feel that a diagnosis of a lifelong disability like this is something to be mourned. But for us as parents, it was like the sun had started shining for the first time, and we were given access to the knowledge, capacity and the tools to understand our daughter, and to properly support her.

After the diagnosis I started to read. I read and read and read. Every textbook, parenting manual and online resource for parents with a child with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder), and while I was reading, I saw clear examples and parallels not only with my daughter’s behaviour, but also with people I work with – clients, collaborators, stakeholders, engineers, lawyers, designers like me… you name it. If it’s in the text book – I can show you people all around me who share those characteristics to a greater or lesser degree.

We all make light of the idea of ‘being on the spectrum’ when we observe idiosyncratic behaviour or social and emotional extremes, but in reality, a formal diagnosis of ASD is not uncommon and indeed is on the rise. In Australia about one in 100 of us are diagnosed and of those in adulthood, only 20 percent are employed and so are significantly underrepresented in the workforce. However, the range of neuro-diverse conditions goes well beyond ASD and Asperger’s, and includes people who suffer from ADHD, dyslexia, Tourette’s, epilepsy, to name a few, and it is thought that as many as one in 10 people are neuro-divergent.

The spectrum of human brain function and behaviour is both deep and wide, and each of us occupies our own a unique place on that spectrum. Even for normal (neuro-typical) people at some point in life, at least one in four (and up to one in three in the UK) will experience some kind of mental health condition such as anxiety, depression or stress. Due to widespread under-diagnosis, which when overlaid with the cultural stigma of speaking up and asking for help, more than half of those on what are considered neuro-diverse areas of the spectrum aren’t even aware they are.

What I was beginning to understand is that the clinical boundaries between being neuro-typical, experiencing mental health issues, being ‘on the spectrum’ and having a clinical diagnosis are far murkier, overlapping, and common than I had previously thought. In almost every team, every group, in most meetings you go to, there will be someone who fits that profile, who behaves, feels, thinks, speaks and learns differently to most other people.

My research helped to crystallize something that had always sat in that weird intangible space between my conscious and the sub-conscious mind, a half formed, vaguely uncomfortable feeling. In designing even the best contemporary, most enabled and functional workplaces, even caring deeply about balancing the needs of introverts with extroverts, we have spent the better part of 20-years looking at ‘workstyles’ to figure out what facilities and types of experiences and spaces people need to be their best at work – and broadly speaking, workstyles are based on a title or a job description that a person happens to hold, rather than an individual’s personality and their neurological differences and preferences.

In 2012 when Susan Cain’s book, Quiet arrived, it was a trigger to our industry to purposefully think, act, and design around one of the most fundamental dimensions of a person’s personality – whether you are an introvert or an extrovert. We are constantly bombarded with messages that to be great is to be bold, assertive and confident, and that being sociable is the path to happiness and a fulfilling life. Through that singular behavioural lens, Cain highlighted how the 20th century has shepherded a ‘Culture of Personality’ into dominance over a ‘Culture of Character’, a significant impact of which is how often introverts are passed over and under-supported in workplace environments, cultures and society at large in lieu of their more eloquent, bolder and charismatic extrovert cousins.

Interestingly, evolutionary biologists have discovered that the behavioural characteristics of the introvert (cautious, slow, quiet, wait-and-see) and the extrovert (fast, loud, just do it, jump in head first) are replicated not only in humans, but can also be observed in over 100 animal species such as primates, cats, dogs, goats, birds, some fish and many insects. There seems to be an evolutionary purpose and latent survival strategy in balancing out and supporting diverse personality types – something society at large could learn from.

So after seeing the genuinely radical transformation in my daughter following her diagnosis, in large part due to our increased capacity to shape her physical, sensory, behavioural and emotional environment to support her better – my two worlds started to collide, and I asked myself – what can we do to design workplaces to better suit the physical, sensory, behavioural and emotional environment of a much broader range of people than we currently do? What if we sought to go beyond the narrow lens of introvert/extrovert? What if we designed our workplaces and shaped our cultures around a much broader and more equitable definition of diversity – beyond gender, race, religion, physical ability, sexual preference, and age, beyond the introverts and their quiet rooms, and started to take into account people – actual people’s – neurological differences?

The good news is that some organisations are deliberately seeking out and nurturing the diverse abilities and gifts of neuro-diverse people not only to support diversity, but because it can bring significant performance advantages. This is leading to a range of more inclusive policies, programs and procedures in many organisations. Though this recognition is in its infancy in the realm of workplace design, according to Cain some of the most effective teams consist of symbiotic introvert-extrovert relationships, in which tasks are undertaken according to each group’s natural strengths and temperaments.

In my own experience, organisations such as Macquarie Bank and Clayton Utz actively seek neuro-diverse people because they often possess exceptional talents when it comes to innovation, creative storytelling, empathy, design thinking, pattern recognition, coding, and lateral problem solving, however none have consciously altered their working environments to meet neuro-diverse needs.

There is a school of thought that embraces the idea that neuro-diversity may be every bit as crucial for the human race’s evolutionary development as biodiversity is for life in general. Both my daughter and, from all accounts, teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg have more concern and empathy for the natural environment than they do for people, and it is certainly possible that their singular focus, their analytical, logic and fact based arguments, combined with (internal) passion and an unrelenting drive to action may well be the only thing that moves societies to act in anything other than our current dominant mode of pure self-interest.

I now passionately believe that those of us that conceive and create the stage for people to work need to be much more aware of and sympathetic to the idea that one size doesn’t fit all, but further, we need to be designing workplaces, and indeed all places, with a deep understanding and consideration of neuro-diversity and the goal of greater inclusivity. We need to think more carefully about how the physical environment impacts not only our sense of wellbeing (physical and mental, which are clearly incredibly important; and much more commonly aspired to) but also for emotional, sensory and neuro-wellbeing, which must go far deeper than simply providing a poky quiet room for every 15 people or so.

So what can be done?

Well, it’s hard. Culturally, our current way of life places a very high value on extroverts – those willing to be on display, to be visible leaders, those who are natural networkers and can make small talk with anyone, anytime, and who often can talk the legs off a chair. As designers, we love to design for these people as the spaces that suit tend to be more architecturally dramatic, open, visible, connected and transparent. As an industry we need to be more willing to understand and be sensitive to what makes people tick, how to support both functional workstyles and individual personalities in the work people do, and to continually strive to find ways of creating places that enhance and support emotional and neuro-comfortability.

The open office that has been evolving from the 1960s has taken the idea of solitude and retreat and virtually abandoned it. Every minute of every day provides an open invitation to approach people quietly working away, and interrupt them. Even for neuro-typical people, the sheer impact on productivity from being interrupted from a period of deep thinking is huge – imagine how much worse it is for ASD people who find it difficult to filter background noise, who may like the idea of working within a team, but who only have a small capacity for it and rapidly get (as my daughter does and if I’m being honest, I do too) “all people’d out”.

Contrary to popular belief, offices aren’t inherently evil. Those (some consider lucky) partners in law firms who represent the last bastion of private, enclosed, individual space who ask for a door and some walls in order to be highly productive and comfortable at work trigger all sorts of trauma for others – who themselves generally don’t need those boundaries to thrive. Cue the old arguments about walls being ‘bad’ because they allow people to use space as a measure of hierarchy. It’s no accident that law firms, the last frontier of the office, also anecdotally have a very high incidence of ASD and ‘on the spectrum’ employees. Firms such as Clayton Utz in Sydney and Linklaters in London have recognised this and are specifically employing people for their neuro-diverse talents.

“Neuro-diversity need not be a barrier to working at a world class law firm. In fact, embracing the diverse talents of people in a diverse workforce enables us to deliver the best possible service to our clients,” says Owen Clay of Linklaters .

Over in non-legal organisations, in the name of financial efficiency and through a traditional lens of ‘workstyle’, agile and ABW environments have required people to do away with ‘owned’ space – asking them to abandon routine and certainty which for some brings safety, predictability and which allows them to function in a confusing and challenging world. For some – this is great – the workplace as a platform for an ever-changing performance breaks the monotony of the 9-5 existence and recharges their extrovert batteries, but for others, this is kind of environment is pure torture. Interestingly though – I believe that the only possibly spatial strategy that can come close to supporting neurological inclusivity is an ABW one.

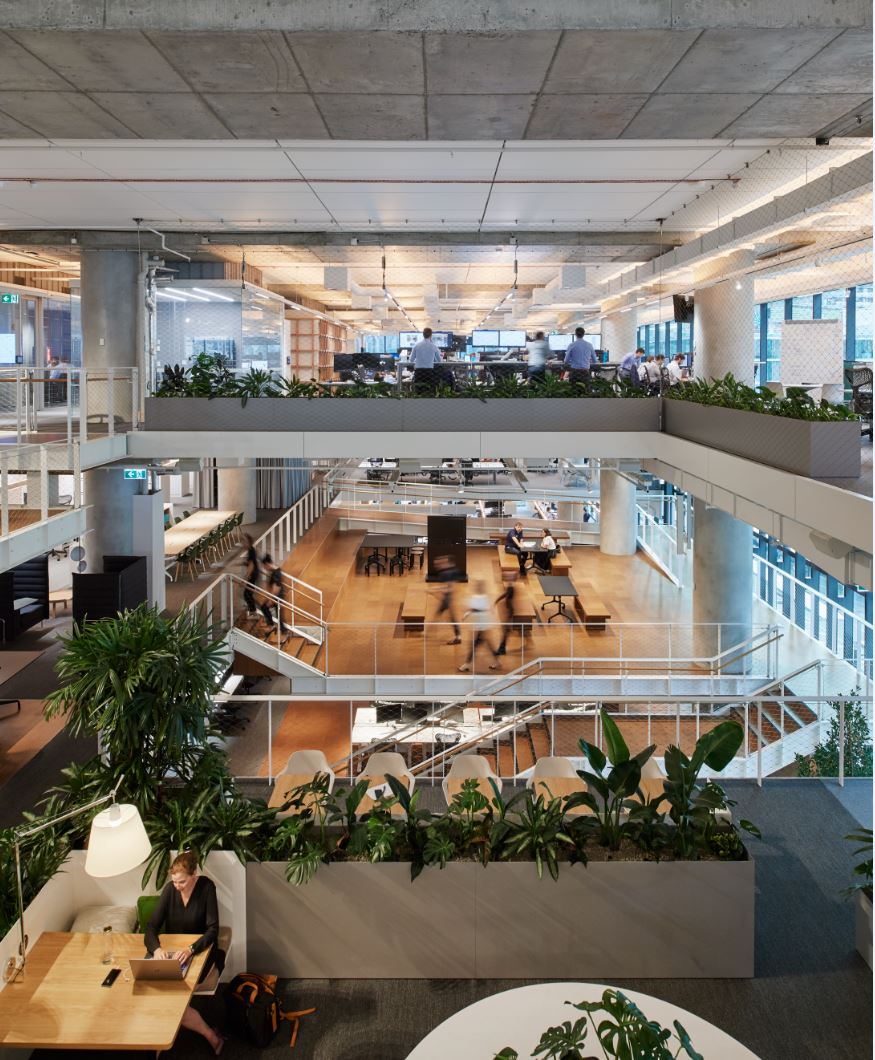

Diverse, plentiful and genuinely differentiated places to work that can enable people— neuro-divergent and neuro-typical alike—to manage their own needs with dignity and autonomy is what we now need to work harder on – remembering that in Australia we arguably already lead the world in contemporary workplaces that provide choice and enable people and cultures to thrive. Providing more choice and diversity in the kit-of-parts that we use to enable the best workplaces for the most people must be part of the solution.

There can be no doubt that atriums, voids and staircases are connectivity gold, but they also have the effect of placing people firmly on display. They actively cultivate the idea of the workplace as a stage – a platform for performance. Being seen and being seen to be seen. The neurological reason that almost 75 percent of people experience anxiety and fear from public speaking is that from an evolutionary perspective, the only time on the African savannah we were ever really subjected to intense observation is when we were being stalked by hungry lions. This sense of being ‘in the crosshairs’ triggers our instinct for fight or flight, and our bodies tense up (my daughter rocks from side to side and talks to the floor when forced to speak publicly), we start to sweat in anticipation of needing to cool down, our blood is redirected to our extremities in order to run, literally, and our capacity for rational thinking and recalling non-life preserving information is sidelined, and so some people go horribly blank in front of a group of people. Being visible and on display in a workplace for people who are on the ASD and introvert end of the spectrum triggers the same physical and emotional responses, which isn’t likely to lead to great productivity or a sense of being supported.

But, by far the most common areas that can be improved on in workplaces to cater for neuro-diversity centre around sensory experiences. Neuro-diverse people can often be highly sensitive to factors in their environment such as lighting, sound, texture, colour, pattern, smells, temperature, air flow, enclosure, air quality and an overall sense of spatial security which can be influenced by clear orientation, intuitive circulation paths and graphics based wayfinding.

Over lit spaces that use fluorescent troffers at 320 lux should be shamed out of existence for everyone. Spaces that embrace movement and allow for standing and walking meetings should be embraced. We should be more deliberate in our use of textures and colours to deliberately calm, excite or activate a variety of emotions and moods. The ubiquitous quiet room should be given a complete makeover – from the traditional desk and task chair for concentrated knowledge work, to comfy darkened lounges that enable stretching out to think and read, to anechoic chambers where your music can be played as loud as your ears can bear, greenhouses where you can truly immerse yourself inside a world of softly moving air, plants and butterflies, or even (as we recently created for a pharmaceutical client), a rain room, where you can stand in the middle of a building and experience the sensory joy of falling rain on your face… these are all ways we can create more inclusive, and more sensory diverse places to be.

I certainly don’t have all the answers – and I’m not sure we ever will as humans tend to be infuriatingly diverse and ever-changing, but that’s no reason not to try to make the workplace a better, more beautiful and accepting place for a diverse range of people. I know I will be trying to, so I can help to make the world a better place for my daughter to not only to be accepted into, but to thrive in.

Wow. Thank you. Lots of my coworkers are easily ‘peopled-out’ and it’s refreshing to see someone else echo what we have been trying to achieve. There has to be a variety of spaces – not just a variety of places to sit that are all the same. 😉 We need to honour the individual – the need for privacy, the need for stability (I know where I sit every day), the need for interaction and the need for excitement. We can do it – it’s just not as easy as pretending that everyone needs to collaborate in a large open space.

Love this article, that so neatly lays out why we need to take this into consideration during design. I want to know more about the rain room 🙂