Pandemics spawn innovation, but they are also exceedingly difficult to navigate. Leigh Stringer asks: How can we, as designers of the built environment, play a role in shaping what’s next?

Historically, pandemics have spawned innovation in everything, including science, art, architecture, technology, fashion, and public health. They force us to rethink our preconceptions and test new ways of not just reducing suffering from disease but also improving our way of life. Interestingly, how we address pandemics can be connected to what we believe at the time caused disease. We can see evidence of these changing beliefs in our cities and in our buildings.

From Miasma to Germ Theory to Behavior Change

Through the 1300s and well into the 1800s, there was a widespread belief that diseases such as cholera, chlamydia, and the Black Death were caused by miasma, a noxious form of “bad air” emanating from rotting organic matter. Addressing miasma can be traced to elements in the built environment we still see and benefit from today, such as wide and crested streets that flush off pools of standing water, irrigation systems that distribute fresh water, and green space to clear disease from heavily populated areas. Fredrick Law Olmstead, a strong believer in miasma theory, advocated for the healing power of parks, which would act like urban lungs and “outlets for foul air and inlets for pure air.”

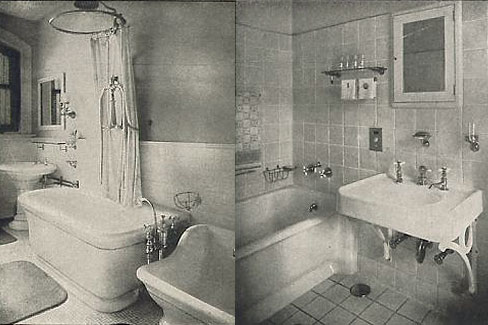

In the late 1800s, germs became the culprit. Germ theory, the idea that infectious diseases are due to the agency of germs or microorganisms, started catching on. Major scientific breakthroughs and the need to address epidemics like the Spanish Flu, tuberculosis, and yellow fever, catalyzed a series of building and design inventions that are also common practice, and still found in homes today. Bathrooms after 1918 moved away from clawfoot bathtubs and wallpaper – both of which were hard to clean of germs – and instead were replaced with built-in tubs and subway tile walls that could be wiped down easily. In the 1930s, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal required all apartments have fire escapes, main hallways that were three feet wide, and separate bathrooms, all in order to reduce the germ spread in more densely populated tenement housing.

The last twenty years have taught us that while addressing germs are important, our behavior can also help reduce disease – both communicable (like pandemics) and non-communicable (like diabetes, heart disease and other chronic issues). A recent boost in health research is now informing how we design urban environments to encourage walking, biking, and social interaction and how we shape indoor and outdoor spaces to encourage movement, flexibility, choice, and generally improve mental and physical health.

Enter COVID-19

With the dramatic rise of coronavirus since early this year, designers, facility managers, and human resources departments everywhere have been hanging on the words of epidemiologists and building on healthy best practices to date. But the sheer volume of research and data, and the professional responsibility we bear can be overwhelming.

Access to real time data about the virus means we are responsible for checking and knowing about its every move. We have to be conversant in a new vocabulary, including technical terms like quarantine, droplets, fomites, aerosols, contact tracing, R-naught value, and herd immunity. And the expanding mix of building guidelines and mandates we have to follow – the latest from the CDC, WHO, OHSA, ASHRAE, AIA, WELL, Fitwel, local jurisdictions, etc. – means we are constantly checking and rechecking that we haven’t missed anything new and important.

Add to this data overload the fact that there is strong disagreement about where coronavirus will take us. Some believe that things will go back to normal once we have a vaccine, others predict COVID will transform everything about how we live and work in the future, and many vacillate in the middle somewhere. This ambiguity, puts designers and innovators in a bit of a quandary. We’re desperately trying to help our clients get back in business – installing sneeze guards and hands-free door openers, buying PPE, upgrading filters, and moving walls around – but these strategies are really costly at a time when money is tight. How can we make useful decisions when things are so up in the air?

New Ways of Thinking

This period in history, for me, is at the same time terrifying and wonderful. COVID-19 has weakened our economy, disproportionally impacted the poor, shaken up the workforce and created anxiety, fear and mistrust. But really, the coronavirus has done what every other pandemic in history has done. And, like other pandemics, has revealed biases, assumptions, and the fragile and intersectional connections between the systems that sustain us. It is the ultimate catalyst for change, which makes now a great time to test new healthy possibilities and let go of things that were not working so well for us anyway.

It also requires that we adjust our approach to design, which is leading to a whole new set of ideas and innovations. Here are eight to consider:

1) Balance changes in the built environment with flexible work policies.

The solutions that work best require a combination of physical changes and behavior modifications. Physical changes, like changing out filters, moving around furniture and adding signs are good and important, but behavior changes, like allowing workers to do their job remotely or in shifts are just as important to reducing exposure to disease. Working from home or flexible work used to be a “nice to have,” but now it is a strategy to save lives. This really changes the conversation about what is really business essential, and opens up opportunities that might not have been possible in the past.

2) Address psychological safety.

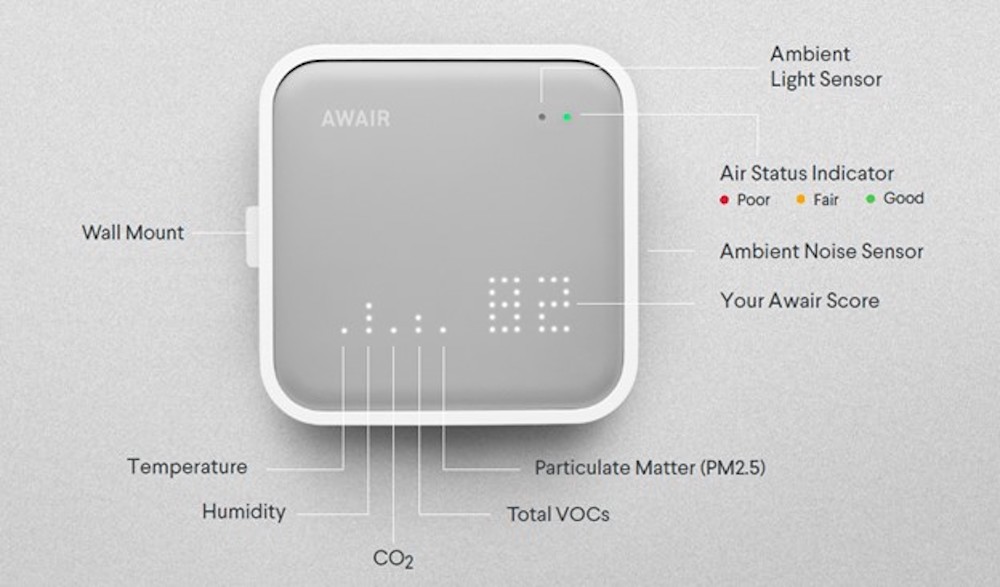

There is mistrust about the many and varied strategies out there to address COVID and keep people safe. Ironically, some of the most impactful safety features in our buildings are out of view – like good humidity levels and outside air filtration systems. As good as they are, because we can’t see them, they don’t always help us feel psychologically safe – a critical component to our mental health. We have to find ways to make the invisible, visible.

Consider “showing” how spaces are being cleaned or proving that they are safe to occupy. In my office in DC, we’ve placed AWAIR sensors throughout our floors so that we can see in person and remotely from our phones the CO2, humidity and other air quality measures of our space in real time. We are using the data to make informed recommendations on upgrades to our HVAC system, but it is also helping us adjust our behavior – if CO2 levels go up in one of our conference rooms, we either open the windows or leave the room. (For the record, these rooms are used only for business essential meetings right now!)

3) Nudge AND tell.

One behavioral issue you might be keenly aware of in grocery stores, on the street and even in your office, is the difference in people’s interpretation of the six-foot rule. No matter how many times we say it, people are just not keeping their distance all the time. To be fair, most indoor and even outdoor spaces were not designed with social distancing in mind, so it’s easy to fall back into old habits. As the communal spaces we occupy start to increase in density, it becomes particularly important to build in strong visual cues along with regular communication, nudging safe behavior and making healthy choices intuitive and easy. This can happen through clear signage, furniture configuration, hands-free fixtures, or literally putting up walls or barriers to encourage movement in a certain direction.

4) Design “outside” the box.

A whole new generation of workers has learned about the power of nature, especially during these last few months. They have been able “expand” their work environment beyond their home office and take advantage of the best free workspace ever – the outdoors. Turns out the outdoors has a better air quality than many indoors these days. Being outdoors is great for our mental and physical health, our creativity and our performance, and particularly important to address now, given the increased amount of indoor time we are all spending during the pandemic. It is also a great time to find ways to bring more of the outside indoors.

5) Embrace, filter and leverage data.

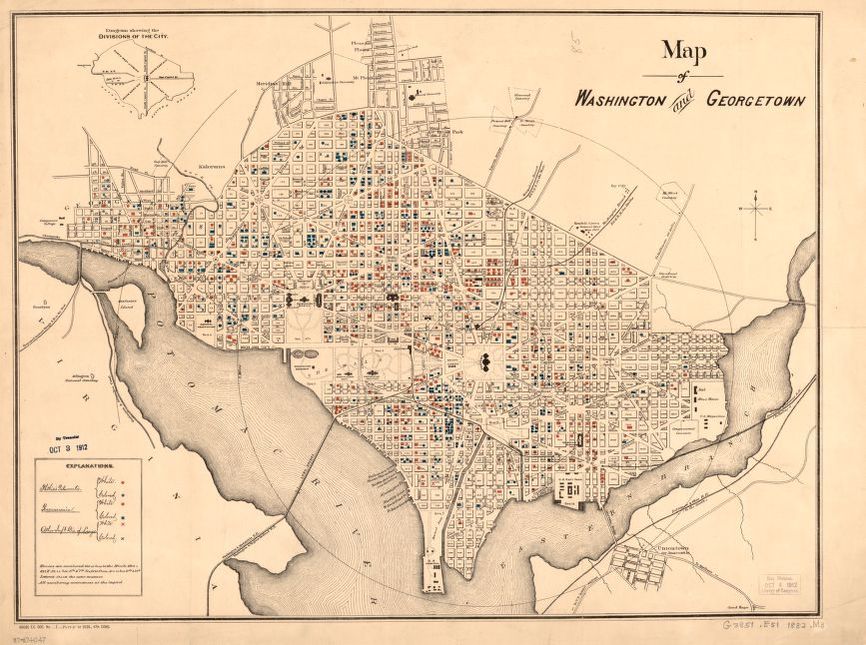

Up until recent history, there was no such thing as “data overload.” There was very little health data and what did exist took an exceptionally long time to collect. I was recently nosing around on the Library of Congress website looking for old maps of my neighborhood and ran across this one of Washington and Georgetown from 1882, with hand markings showing cases of tuberculosis, pneumonia and other pulmonary diseases. This was the smartest, and most efficient way to collect data at the time.

Fast forward to today, when we can see global data barely a day old, graphed and charted in infinite ways right before our very eyes. These incredibly powerful visualization tools allow us to track and treat communicable (and non-communicable) disease much more quickly than years past. Data can tell us in real-time whether a space is safe or not (reducing infection and caseloads in hospitals), and also how to best support our health and wellbeing beyond the pandemic. The possibilities are endless and we’ve only scratched the surface.

6) Think of buildings as an instrument of public health.

We’re already seeing technologies that remotely measure body temperature, occupant counters that show you on a monitor whether you can enter a room or not based on capacity targets, and doors that sense presence and automatically open (like hospitals) when you walk up to them. If you are thinking our buildings are starting to sound like something you might see on a Star Trek episode, you are not that far off. (Try a Google search of “things on Star Trek that actually came true” if you need some inspiration.)

The thing is, our buildings before COVID were full of opportunities for the spread of disease, and we put up with it because the stakes were not as high as they are now. But there are so many small design changes that can help reduce sick days and keep building occupants happy and more productive, like this simple capacity counter by a bathroom.

7) Seek out design-adjacent partners.

Moving forward, just like during other pandemics throughout history, we are likely to get engaged in big issues that take us outside of our swim lane. Design teams are working in lock step with policy makers, ops and technology experts, epidemiologists, safety experts, mental health counselors and others to understand the full implications of their recommendations. Make space for people who think big and come at problems from a different direction.

8) Take deep yoga breaths and slowly count to ten.

Complete and systemic change takes time to work itself out. It is unrealistic to expect that after less than a year in this pandemic, we know everything that will happen (and anyone who suggests otherwise is selling something). But if history is a guide, good things will come of this period of questioning and discovery. Out of the Bubonic Plague came the Renaissance.

We cannot change the future, but we can change our attitude about it. The future is bright for anyone who contributes to shaping our built environment and willing to challenge the status quo. To quote Dr. Richard Jackson, former Director of the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health, and advocate for the influence of the built environment on physical and mental health, “We humans often assume that what is, had to be that way. In reality, virtually everything in our built environment is the way it is because someone designed it that way.”