From Roman bathhouses to touchless office toilets, restrooms have always reflected society’s values. This World Toilet Day, PLASTARC explores how inclusive, biophilic, and gender-neutral restroom design can elevate everyday workplace experiences and reflect a culture of care.

We’re used to commemorating civilizations for their notable achievements: the art they produce, their most iconic leaders, their fashion, and architecture. But one simple, perhaps crass touchstone – how civilizations handle their waste – might actually offer more insight into the lives led by their citizens. In the same way that Roman bathhouses and royal garderobes provide insight into historic societies’ cultures, so, too, do today’s touchless toilet stalls. Though it may seem like an afterthought, the design of a restroom reflects some of a culture’s most essential fabric.

World Toilet Day (November 19th) is always a sobering reminder that much of the developing world still lives without easy access to a toilet, and that there’s much work to be done to cultivate healthier, sanitary living conditions for those communities. At PLASTARC, we also use this day to reflect on the ongoing evolution of workplace restrooms, and how our professional vocabularies around biophilic, human-centered design can be directly applied to a space that’s so often dismissed as mere necessity. How can we, as workplace consultants, help businesses design and implement restrooms that elevate the worker’s day-to-day experience? When considering the broader historical context, we come to recognize that changes in restroom design can both encapsulate and inspire shifts in our social customs: How we flush, wash, or “freshen up” reflects how society defines dignity, gender, and privacy at this moment in time.

The Evolution of Sanitation: From Social Act to Private Matter

Long before single-use, gendered restrooms came with a deadbolt to guarantee the user’s privacy, Ancient Rome’s communal latrines featured long marble benches with multiple openings. Citizens would comfortably sit side-by-side and casually chat while doing their business. Contrary to modern customs, hygiene was a deeply social activity – the latrine was a known hub of social exchange. To “go” in company was, quite literally, the civilized thing to do.

Centuries later, Medieval Europe continued this tradition: Royal courts often included garderobes where noblemen relieved themselves during meetings, seated shoulder to shoulder. Kings were known to hold counsel mid-defecation. Instead of being sources of shame, bodily functions were simply a fact of life, and the act of relieving oneself among peers was far from extraordinary.

That communal ease began to erode with the introduction of the outhouse. The separation of a space specifically dedicated for people to “take care of their business” marked both a physical and psychological distancing from waste. Suddenly, basic bodily functions were a private matter. This shift mirrored Europe’s broader societal framing of cleanliness as both a moral imperative and a mark of one’s class. Physical distance from one’s waste, manifested in new design choices, communicated civility and refinement.

The Modern Restroom

By the turn of the 20th century, the introduction of indoor plumbing had culminated this shift. Waste was whisked underground, completely out of sight. The newly christened “water closet,” a triumph of infrastructure and respectability, became a cultural staple, and the ability to flush privately was seen as a hallmark of progress. Those same functions that were once performed in social contexts amongst royalty were newly relegated to the most private corners of daily life.

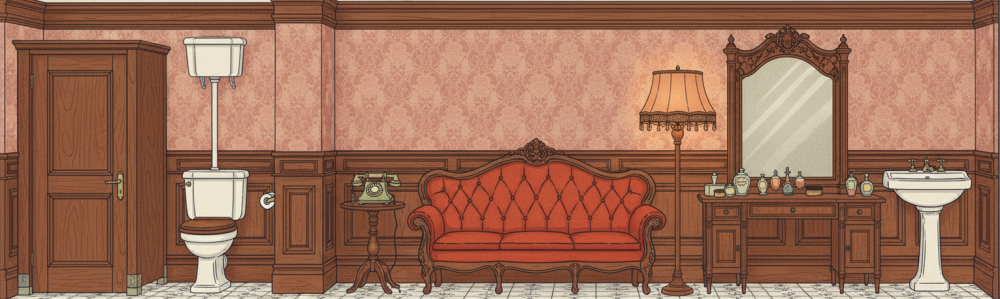

And just as flushable toilets were becoming popular, so were gendered restrooms. In a world where Victorian sensibilities still held cultural clout, women’s increasing inclusion in public institutions like offices, universities, and factories necessitated architectural segregation along gendered lines, since women’s bodily functions were considered too improper to share with men. The division of “Men’s” and “Women’s” facilities, though, also inspired a re-emergence of social spaces that revolved around personal relief. Women’s facilities, from department stores to train stations, became something of a sanctuary; upholstered sofas (aka fainting couches), armchairs, and vanities gave the user a chance to relax and refresh at their leisure. The more luxurious “retiring rooms” sometimes even featured writing desks, telephones, pianos, and cosmetics that ladies could use to touch up their appearances. Retiring rooms – redubbed “restrooms” by the early 20th century – were designed as places to compose oneself, not just dispose of waste. In contrast, men’s rooms tended to emphasize efficiency and utility.

Over the decades, this architectural divide – not to mention the segregation of spaces along racial lines – hardened into cultural expectation. Blueprints, building codes, and signage all reinforced binary norms that linger today, even as women’s facilities increasingly resembled more “practical” men’s rooms. But now, more than a century since the emergence of gendered restrooms, workplaces are actively working to dissolve those divisions, while bringing back spaces of respite for men and women alike.

The Restroom of Today: De-Gendered, More Accommodating

More than a century after gendered restrooms became ubiquitous in industrialized cultures, we are once again in the midst of a sea change. The same paradigm shifts that are transforming our customs around where and how we work are also inspiring forward-thinking organizations to update the function and design of their restrooms: companies like Salesforce and Microsoft have introduced gender-neutral restrooms in their offices, and biophilic design elements such as natural light, wood veneers, and plants are helping to re-imbue these spaces with a sense of comfort and refuge, thereby reclaiming the “rest” in “restroom.”

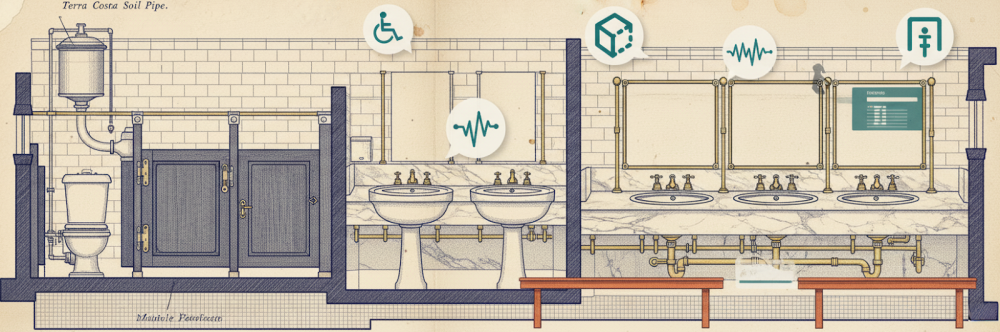

Just as Activity-Based Working Models are intended to uplift the worker’s daily experience, so too are the restrooms of tomorrow. Far from being an exception to the rule, restrooms are part of our broader cultural pivot from “compliance-based” architecture to empathy-based design. With that in mind, the modern worker has not forgotten many of the cultural touchstones that came out of industrialization, like personal privacy and basic hygiene. And restrooms, in turn, are elevating those priorities through innovative updates: floor-to-ceiling stalls (exemplified by WeWork) ensure that our toilets aren’t the hub they once were during the era of Roman latrines, communal, nongendered hand-washing areas ensure that the spaces where socialization does happen are no longer segregated, and touchless fixtures – practically universal in newly-built offices – minimize the transfer of pathogens.

The last decade has ushered in a new era of smart restrooms, which use sensors and automation to improve sanitation, sustainability, and user experience. At their best, these systems can make restrooms more hygienic for users and easier to maintain for custodians. Sensors that monitor soap, paper, or water levels enable responsive maintenance, while user-input technology, like the little “thumbs up/thumbs down” or “smile/frown” buttons seen in airports, can help custodial teams account for anything that the sensors cannot.

Some researchers are even experimenting with IoT-based feedback systems that monitor environmental factors like ammonia levels and Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) to trigger maintenance. Some of these experiments, however, go a bit too far by tracking users’ occupancy rates and dwell time. Even if this information is anonymized, the awareness of our status as data points doesn’t exactly bring peace-of-mind while we’re trying to have a moment of respite. When it comes to occupancy, the restroom should remain one of the last unquantified spaces in the workplace.

With that being said, aggregated waste data – handled responsibly – can offer profound public benefit. Wastewater testing has already proven to be one of the most reliable indicators of community infection rates in times of viral outbreaks. As workplaces embrace wellness as part of their building design, anonymized biomonitoring may prove just one of many elements that helps to elevate the health of workers.

Multisensory Considerations

By integrating multisensory stimuli and offering workers a much-needed sanctuary, we can make the concept of the “retiring room” feel far less antiquated. Here are just a few of our favorite multisensory features we think should be integrated into more office restrooms:

- Circadian lighting, to help recalibrate the body between meetings

- Sonic features like sound-masking, to create a sense of auditory privacy

- Scent profiles, to neutralize any offending odors

- Soft tactile materials, to instill a sense of comfort

- Heated bidets, to help the worker feel clean throughout the day

In a time when rest can be hard to come by, a few minutes of composure – whether found in the great outdoors or the quiet of a well-designed restroom – often prove indispensable, both for personal health and daily performance. The restroom of the near future will honor the worker as a discerning user by creating a restorative space. It will use contemporary technologies to restore the best aspects of old models – the retiring room, for instance – while doing away with their more antiquated elements, such as the stark division of gender.

Just as we do any other part of the office, we at PLASTARC are reimagining workspace restrooms from a more holistic, empathic angle. We believe that the next frontier of restroom design will continue to go beyond plumbing and hygiene to create spaces that exemplify a culture of care. Restrooms, after all, have mirrored our collective priorities for centuries – from Ancient Rome to present day, the ways we “do our business” reflect our cultural condition. With enough forethought and care, we see a world in which restrooms are no longer architectural afterthoughts, but reflections of our collective humanity – spaces that remind us, in the most ordinary moments, of our own dignity and the power of great design.