When we design for all types of employees, we also must consider the unknown.

PTSD is the result of a traumatic experience. Our prototype case is taken from an armed combat environment, which represents approximately 8 million people. Taking a look at the larger picture, you’ll see that trauma comes in many forms: abusive relationships, mass shootings, physical assaults, deadly accidents, civil strife and political upheaval. Other events can also lead to a PTSD diagnosis like natural disasters, wildfires, terrorist attacks and even a life-threatening event, which represents approximately 72 million people, and varies by gender and age. In fact, the overall prevalence of PTSD is almost three times higher among women than men.

We hope that the information we present here can be elevated to a larger conversation around the workforce. Technically, our approach falls into the neurodiversity paradigm that is used in the workplace design community to account for psychological functioning and value diversity in neurobiological development. In a contemporary setting, this usually refers to a person’s placement along a spectrum of autism.

But people with PTSD usually do not exhibit any type of early symptoms – there are no warning signs that a person is suffering from PTSD. Although through research, we have determined that there are certain behavioral indicators that suggest a person maybe be suffering. Many people with PTSD have no prior history of mental illness nor do they fit the current definition of someone who falls into the neurodiversity paradigm.

This creates an issue when considering that design should be inclusive and accessible for everyone. When we design for all, we also must consider the unknown. From a practicality perspective, this may not be feasible for some clients unless they are embracing the theory of universal design principals that incorporate aesthetics as part of the design approach. This means that they take into consideration all of the aspects of color, light and form and evaluate these principals from multiple perspectives.

We want to apply this thinking to a wider range challenges that can effect a person’s work style and differential reaction to environments. We are focused here on just one incidence of a psychological syndrome and that focus has been informed through personal experience, not just academic theory. It is our belief that the physical design of work environment can ameliorate some of the more common negative symptoms.

Design Challenges

What got us started down this pathway was a challenge presented by a client about how to design home/workspaces to accommodate people along the neurodiversity spectrum.

To better understand the underlying psychology of trauma and stress we spoke with Dr. Robin Pratt of Enhanced Performance Systems. Dr. Pratt has more than 40 years in the research and development of high performance experimental psychometric cognitive and behavioral assessment techniques. He explained that under high-stress conditions, signals from the environment are overcome by ‘noise’, people become highly distracted, lose their train of thought, and have reduced flexibility.

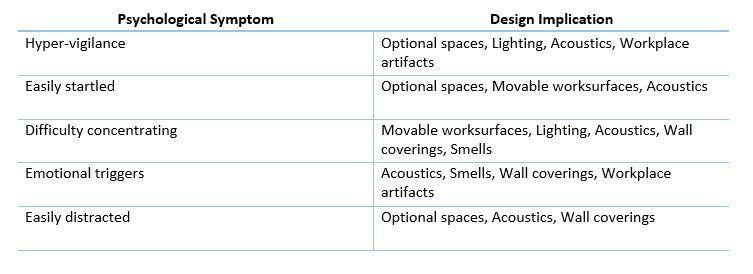

Based on these hypotheses, we have picked five key psychological characteristics of people with moderate to severe PTSD.

- Hyper-vigilance: Always on alert scanning the environment for real and perceived threats. In severe cases this can turn to paranoia.

- Easily startled: The slightest unusual noise, close presence of someone in their ‘personal space’, getting sneaked up on.

- Difficulty concentrating: Closely related to hyper-vigilance. So much intentional energy is devoted to environmental scanning, little is left for the task at hand.

- Emotional triggers: Usually seen as overreactions to other people’s expression. Triggers the flight/fight/freeze behavior.

- Easily distracted: The ‘look another shiny object’ behavior. Affects all five sensory modalities – sight, sound, smell, touch and taste.

Here are some practical design guidelines to improve the adverse effects of each of these PTSD symptoms. These guidelines should be used for general purposes. Those who are suffering from severe trauma or have multiple PTSD symptoms will need more of a personalized approach to their workspace environment that focuses on their specific needs.

In summary, we can link symptoms and design implications.

Implications Expansion

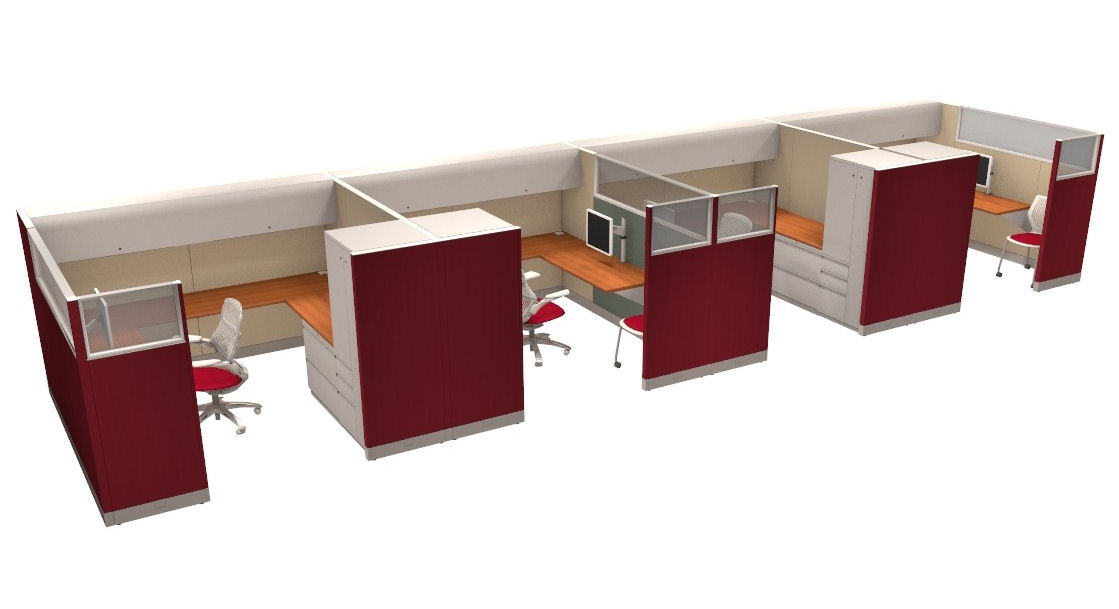

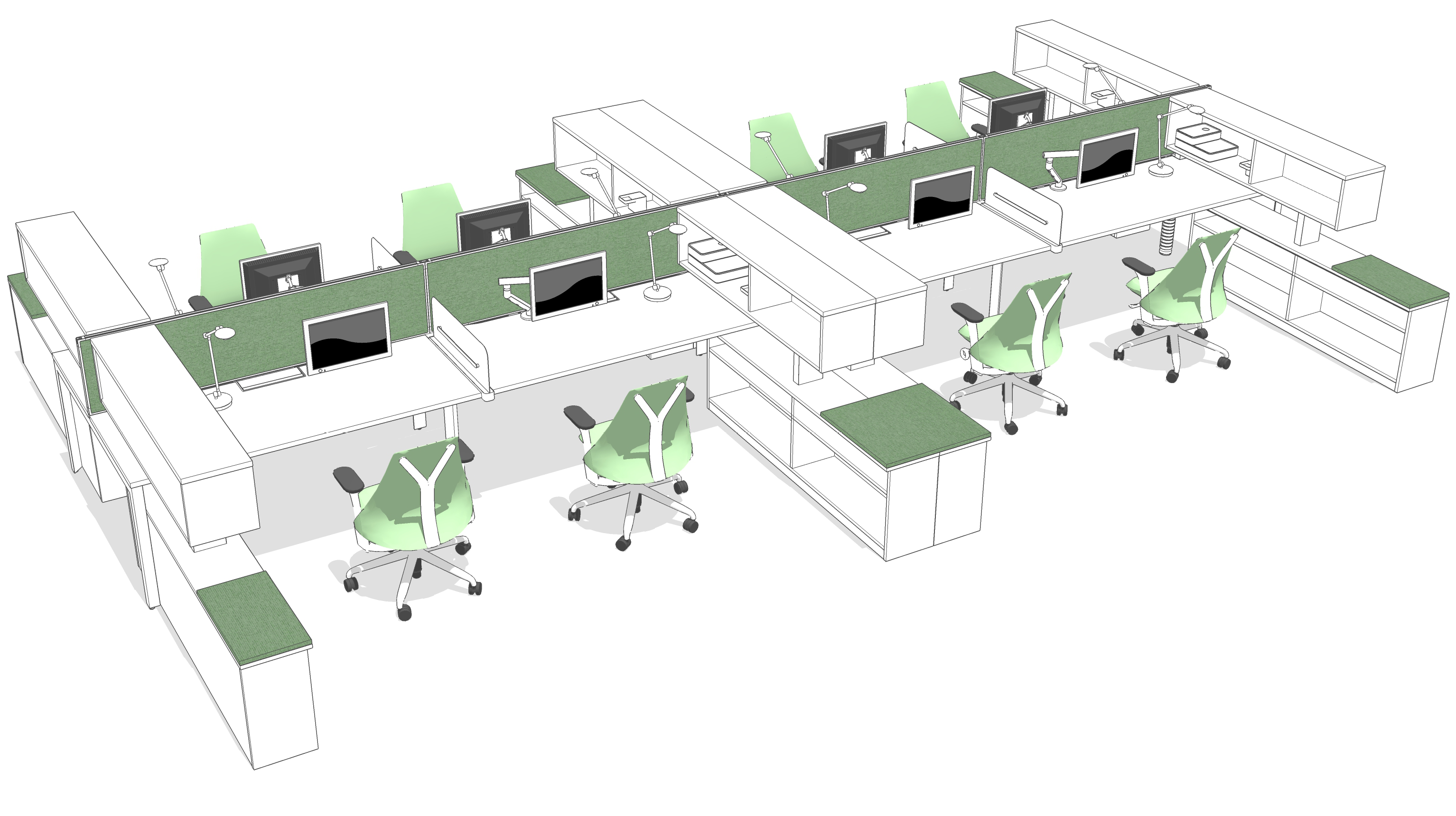

To limit distractions and encourage focus, provide employees with optional spaces to do their best work. Include areas that are easily reached from their personal work areas if the work environment has an open plan. An example could be a small conference room that has doors. The views outside should be of landscaping and not parking lots or back alleys. The lighting should be controllable, and the furniture should be modular and movable. The size of the space should be bigger than a typical workstation cubical (6 x 8) where two to four people can work together but no more than what is necessary.

**Each of the above designs represent a typical office layout that can be modified to accommodate someone who is experiencing symptoms of PTSD.

Worksurfaces and desks should be easily movable or mobile depending on the traffic flow or door location where it can be moved within the area allocated for that particular employee. This allows them to create their own space and meets their comfort level. Chairs should be ergonomically designed. Not all furnishings will pose a problem, but those that do, should be removed or relocated to another part of the facility.

Harmful artifacts should be removed from the work area. Suicidal thoughts are a severe reaction to PTSD. However, self-harm is seen as the next workplace safety crisis. Design guidelines should include the use of anti-ligature furnishings similar to those found in residential behavioral health treatment facilities.

Control of light both natural and artificial needs to be in the hands of the employee. If the lighting in the workplace is typical florescent or LED ceiling grid lighting that covers the entire space, the best way to address this is to have closed areas where the lighting can be dimmed or limited. Lighting that is too harsh or bright can be particularly harmful to anyone who is light sensitive or suffers from migraine headaches. Natural light from a window or a skylight also needs to have some shades or blinds not just to control glare or temperature, but because of the harshness of the light coming into the space can be overwhelming.

Acoustics are especially important. Working in loud environments for any length of time has negative effects on everyone. Controlling noise in an open work environment can be challenging especially if the ceiling is exposed or if there isn’t enough carpeting or other sound absorbing finishes around to lower the sound decibels. Acoustic wall boards and dividers are an easy way to address this issue. White noise or sound masking equipment may not work because of the sensitivity of those who are in the space. They make “hear” the noise masking or have other sensations that are not related to the actual noise like ringing in their ears.

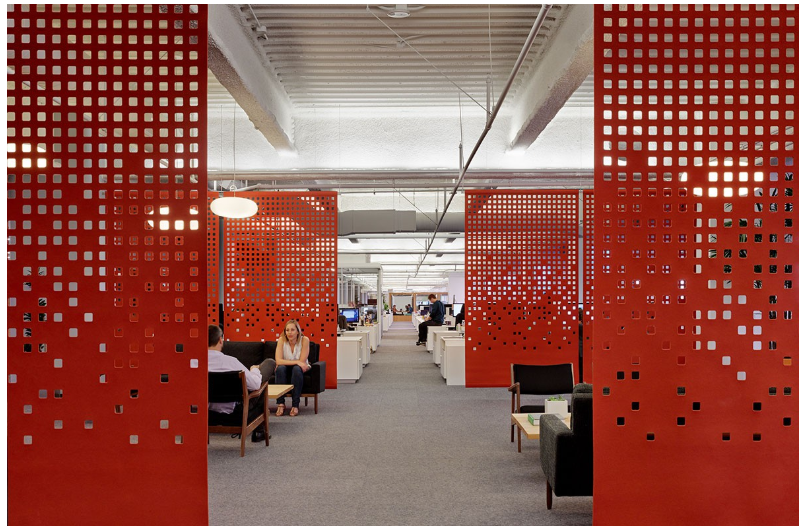

Artwork. Be careful of the wall colors and the art. Images especially have been shown to be triggers for people who have neurological spectrum disorders. This is also true if someone has been diagnosed with schizophrenia, depression or is bi-polar. Harsh colors that are used for accent walls such as brilliant orange, yellow or red can be triggers reminiscent of explosions for example. Images that are blurred or abstract can trigger memories or emotions that are painful. Look for artwork that clearly represents a nonthreatening subject or scene. Stay away from black and white images and graphic modern designs that are considered street art or graffiti. These images although popular in current design trends can be unsettling to a large group of people regardless of their mental state.

Artwork especially photography and graphics need to be clearly defined.

Common office smells from burnt popcorn, old coffee, and even toner ink could be triggers for some who suffer from PTSD. Keeping break rooms and print rooms confined or away from work areas may not be the best use of space, but it does a few things: 1) it gets people moving and 2) keeps these odors from offending anyone who is in the office. Do not use deodorizers or other scented accessories. There is no telling who might be affected by the scent or to what degree the person affected suffers.

Action Suggestions

Although PTSD is covered under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), it can be hard to make a specific determination as to which employees would require an accommodation. PTSD does not necessarily manifest with visible symptoms. It’s psychological state which can lie dormant until triggered.

We suggest an open-ended approach by letting employees know certain accommodations can be made if they do have this disability. Their voluntary disclosure should help avoid any legal action for discrimination. We strongly encourage you to have a senior human resources person as a member of your workplace design team.

Perhaps the most important action you can take is to practice what we call ‘responsible design’. Although interior designers and architects are by no means considered board certified therapists, they are responsible for creating environments that need to be safe. Mental health has been left behind on a number of fronts, including by designers who are responsible for the welfare and safety of those who enter the environments they create. Responsible design is when workplace designers take up the responsibility of conscious consideration of the psychological range of mental health symptoms which may or may not be present among members of the work team. The psychological comfort of employees is just as important, regardless of the costs.

In closing, we must openly acknowledge the elephant in the room. As we alluded to in our introduction this is an issue larger than one symptom (PTSD) and it is more prevalent than the newly discovered ‘neurodiversity’ design approach.

It is the larger context of overall mental health that is important. The built environment does affect our lives and people with various mental health disorders seem to be especially sensitive to these factors. Wellbeing is more than physical comfort – set your design intent to make your work to encompass the whole idea of wellness that includes mental health.

Resources

12 Life-Impacting Symptoms Complex PTSD Survivors Endure

Mayo Clinic -Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Web MD – What Are PTSD Triggers?